How Process Imbues Meaning: Daguerreotypes in Contemporary Photography

( Isabelle Heyward / May 10, 2011 / GRAD 655)

In 2006 Nikon announced that it would no longer make most of its film cameras, shortly after Konica Minolta released a statement that it would be quitting the camera business altogether. A year earlier, both Kodak and AgfaPhoto announced that they would no longer make photo paper (The Economist). The traces of manual cameras and printing from negatives are fading into the past while the use of digital cameras is becoming more pervasive. As Adobe Photoshop and other photo editing softwares are blurring the lines of reality and technique, the photographer is taken farther and farther away from the once laborious photography process. In the modern photographic age, some artists would prefer to shirk the connections between process and product; however, by returning to bygone, labor-intensive processes, such as daguerreotypes, photographers are using process to imbue variations of meaning onto their work. Factors that caused the abandonment of daguerreotypes in the first place are what some artists fine the most appealing. Including the complexity of the process, which starkly differs from the ready availability of modern, digital photography. While artists have different reasons for turning to long-eclipsed processes, they add a layer of meaning unavailable in digital photography, which is consistently beguiled by technology. The use of daguerreotype in the modern age begs the question: how much of the resulting work’s narrative is dependent on the process?

During the first half of the 19th century a boom in photographic technology took place. However, from its inception, the art in photography has been questioned. It primarily filled a need for documentation and portraiture achieving the status of ‘art’ only as a working term. The first photogram was made around 1802. In 1835, Jacques Mandé Daguerre invented the daguerreotype process.

The daguerreotype was introduced to the United States by Samual Morse in 1840, and quickly was embraced as the first form of commercial photography. It allowed the middle class to have portraits taken, something previously reserved for only the upper class that could afford it. The next iteration of photographic technology, the cyanotype, appeared only a few years later. The daguerreotype faded from use after about a decade due to the harmful chemicals it uses and its inability to produce a consistent image (Mallin, 68-73). New technologies such as cyanotypes, tintypes and printing from negatives took the place of daguerreotype. The speed of newer photographic technology pushed use of the daguerreotype quickly into obscurity.

Daguerreotypes produce images whose detail and clarity have never been duplicated. In fact, many of the earlier types of photography are still noted for the depth, texture and character that will never be reproduced or fully mimicked by modern technologies such as Photoshop. The process in making a daguerreotype; however, is fraught with opportunities for flaws. There are clear steps to creating one, however any misstep along the way noticeably affects the resulting image, though these flaws are not apparent until the process is completed.

To make a daguerreotype, a photographer starts out with a thin copper plate, on which they spread an even thinner layer of silver nitrate. This plate is then thoroughly polished and made light sensitive by exposing it to collodion (bromine and iodine). The image is cast onto the plate through a box camera. However, it is not until the plate is exposed to heated mercury vapors that an image appears, through texture, onto the plate. Only recently have two other steps been added to this process: bathing it in hypo (sodium thiosulfate) and a toner solution to make the image permanent (Osterman, 12-15). The daguerreotype was driven from use because of its unpredictability and complexity. However, artists today see these two characteristics as part of the medium’s appeal. Unlike digital photography, which provides an instant image, using the daguerreotype process requires much more time—approximately six minutes for exposure—and thorough knowledge about each step. It is a physical engagement with the process and produces completely unique images (Harris, 64-68).

Contemporary artists first started to turn to archaic photography processes in the 1960s and 70s (The Economist). This, coincidentally, was the same time period in which Poloroid cameras first became

prevalent in the United States. There are many personal stories of why artists turned back to processes like daguerreotype and cyanotype, however the most

widespread is that it is able to further narratives and even create its own within a piece of work. Considering the process and time period from which the daguerreotype was born, artist are able to manipulate meaning in a way unavailable when using modern, instant photography. In the late 1990’s, when turning back to older processes grew into a noticeable practice, the term ‘Antiquian Avant-Guard’ was coined (Rexer, 72-85). A seemingly ironic title, ‘Antiquarian Avant-Guarde’ cannot be applied to all photographers turning back to long obsolete processes, only those who do so with irony, not those who choose the medium solely to reference the time period from which it came.

The George Eastman House, an international museum for film and photography, first started to hold daguerreotype workshops in the early 1990s, around the time digital photography was starting to take off in international markets. In the mid-90s, Mark and France Osterman started The Collodion Journal, a reputed resource for those turning back to the wet-plate process, another term for antiquated processes like daguerreotype. The Collodion Journal serves for many as a reference guide from two practicing artists who spent decades perfecting obsolete processes: becoming historians and masters of collodion photography, even going so far as to print on mica sheets. While Mark Osterman’s work is true to the process, each piece so heavily references the 19th century and early 20th century that it is impossible to see the line between the final image and the process, the fact that it is a daguerreotype seems to dominate the narrative.

Creating nostalgia with an old process can conjure up thoughts of civil war re-enactors. Some modern artists using daguerreotypes are even selling their work as antiques. Artists like David McDermott use daguerreotypes to shoot scenes that look like they were shot in the 19th century. McDermott himself is even known for dressing in 19th century garb (Rexer, 72-85). Using the process as a way to play dress-up panders only to nostalgia and in a way only makes the resulting image less valuable. In these cases, the process then seems more a novelty.

Dan Estabrook alludes to photography’s early years in ‘Interior (Floating Cloth)’. Photography was once likened to a magician’s act and that message is apparent in this piece, which uses visible wires to levitate a piece of white cloth. ‘Interior ’ also alludes to the dubious nature of photography, especially what it has now become with Photoshop and technologies that help to change the reality from which the original image was taken. While this piece is full of messages, which the use of daguerreotype helps to reinforce, there seems to be so much emphasis on the process, the aesthetic creativity is only of secondary importance.

Dan Estabrook alludes to photography’s early years in ‘Interior (Floating Cloth)’. Photography was once likened to a magician’s act and that message is apparent in this piece, which uses visible wires to levitate a piece of white cloth. ‘Interior ’ also alludes to the dubious nature of photography, especially what it has now become with Photoshop and technologies that help to change the reality from which the original image was taken. While this piece is full of messages, which the use of daguerreotype helps to reinforce, there seems to be so much emphasis on the process, the aesthetic creativity is only of secondary importance.

What are the implications for turning back to a process that is difficult, dangerous and highly unpredictable? In the digital age of photography, when film and photo papers are on the verge of extinction, a movement back to photography’s roots references the Pictorialism movement of the late 19th century, which reached its height in the early 20th century. During the Pictorialism movement, photographers approached the camera as a tool, like a paintbrush, that could produce artistic expression. They sought to fight the use of photography for its literal and documentary functions and instead use it for “personal artistic expression” (1911 Encycolpedia Britannica). Pictorialism was a direct response to the industrial revolution, and the modernizing of creative methods.

Daguerreotype can be used to gain a unique and painterly manipulation of an image that has nothing to do with Photoshop or contemporary photographic technology. A contemporary backlash of the industrialization of design and artistic expression can be found in other mediums as well, especially in Dutch industrial designer Tord Boonjte’s designs. Boonjte’s Rough-and-Ready Chair is an example of a piece that strives to offer a personal meaning between the object and its user through a hands-on creation process (Poyner, 58-63). The consumer is charged with the task of making the chair, and in doing so, they eclipse their role of consumer and create a unique sense of ownership with a piece of furniture often created in mass quantities in factories. Parallels can also be drawn between the resurfacing use of daguerreotype and the use of the letterpress in modern printing. The also archaic and time-consuming process of letterpress emphasizes the amount of time the artist spends with the product, which increases the value. Letterpress, like daguerreotype, also provides detail that modern printing technology strives to duplicate.

Unfortunately, selling daguerreotypes made in the 21st century is not a statement by modern artists about how people view process as it relates to value. Today, in thirty minutes, one can get photos taken with their digital camera, printed out at Target. To make the process even easier and involve the photographer even less, one can send their image files via the Internet and get printed pictures mailed. Even printed pictures are fading into obscurity. Plug in photo frames that cycle through digital images are becoming more prevalent. What does this say about how we currently value photography? Has the accessibility and ease when it comes to taking a picture deteriorated the value we put on photographs? If it did not, would there be a movement of artists who have returned to the labor-intensive and dangerous process of making daguerreotypes?

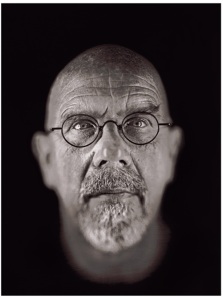

Jayne Hinds Bidaut, a contemporary photographer—who first turned to daguerreotypes and tintypes to photograph her entomology collection— uses antique velvet cases for the images she takes, doing so, gives the images more value (Rexer, 72-85). Bidaut is known for staying true to the older process, however some contemporary artists incorporate modern technology to enhance their products. Chuck Close, who has worked with Jerry Spagnoli to use daguerreotypes for portraits is an example. In his series of torsos, Close incorporates visual references to the modern time in which he works: evidence of surgical scars and tattoos. As one can see in his 2006 Self Portrait, Close gives daguerreotypes a kick in clarity and texture with the use of high-intensity strobe lights to bring out even more detail than the medium already allows. By using newer technologies, artists such as Close can expand on the medium’s image capturing possibilities (Harris, 64-68), however, if the process is often used to further meaning, then what does changing the process say? By changing the process to enhance it beyond its original capabilities, one could conclude that Close uses the daguerreotype primarily as a process, not as part of his story. In concentrating on the aesthetic attributes and the technique it requires the artist to produce an image, Close takes on the role of craftsman. He ascribes to the idea that making a hands-on, one-of-a-kind object makes it more authentic and states that the daguerreotype process is “…an uphill struggle to get an image that you want with any predictability,” (Harris, 64-68). Close has been working with Jerry Spagnoli for years to perfect the process and chooses the daguerreotype to emphasize the focus and clarity available in the medium (Harris, 64-68)). Within his work, there are no subject references to the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Similar to Pictorialism, the use of daguerreotype is a romantic response to the disappearance of human affect in the image taking process. Where photography in the digital age emphasizes information within

the image (graphic or iconic imagery), the daguerreotype process emphasizes the relationship between the subject and the medium, which intensifies personal meaning (Rexer, 72-85). However, when the

two compliment each other—subject and process—a truly successful piece is born.

While the use of daguerreotype by contemporary artist has the ability to create a postmodern piece, this is only possible if the artist uses the medium with irony. Jerry Spagnoli—a master of the daguerreotype

process—uses the medium in a postmodern way without modifying the process. In his Machine for Destroying Daguerreotypes, Spagnoli places a cherry blossom and a daguerreotype print inside a box with a peephole. As the flower decays, it off-gasses and affects the metal plate that the image rests on, ultimately destroying it (Rexer, 72-85). Spagnoli uses the process to create a narrative in the piece, wherein the image on the daguerreotype —which isn’t notes by The New York Times—isn’t even important. Spagnoli’s uses the medium as the subject, but one has to wonder how the image on the daguerreotype could have supported his narrative that beauty and permanence are incompatible.

Candy Cigarette. From the series « Immediate Family », 1991 © Sally Mann, Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, New York

Sally Mann is an example of a postmodern photographer who has gravitated to daguerreotypes. She has been using them in her work for the most part of the last decade and has not modernized any of

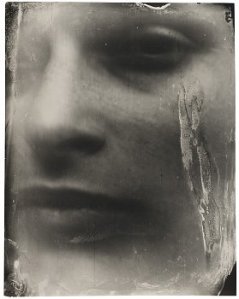

the steps to enhance it; she even uses 19th century lenses when she can. Mann rose to notoriety with her 1995 series, Immediate Family, in which she photographed her children at their home in rural Virginia. With Immediate Family, Mann was both criticized and lauded for her black and white depictions of her children’s daily lives. Her children are again included in her show, Flesh and the Spirit, at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond. These daguerreotype images starkly contrast Immediate Family in many ways, most immediately noticeable in their presentation. The series focuses in on her children’s faces, and the prints themselves are a large format: over four feet high on average. Whereas Immediate Family showed daily scenes, caught in an instant in a predominately 8”x10” format.

The viewing experience for a daguerreotype is different than any other photographic image in that it is based solely on reflected light, so that while five people look at one large-format print from Flesh and the Spirit, all five will see something slightly different based on their angle to the print and the reflected light. Mann uses the daguerreotype medium to give the viewer a more personal connection to these images of her children, possibly as a reaction to the misconstructed meaning some media outposts construed from images of her unclothed children in Immediate Family. While the technique itself produces an image on a smaller silver plate, photographers are able to transfer the daguerreotype

to a larger plate, as Mann has done in Flesh and the Spirit.

In the daguerreotype portraits of her children, Mann uses the process to create utterly unique images that reflect the bond she has with them. Taking six minutes to process, a daguerreotype doesn’t just capture an instant as digital cameras do; they capture a passage of time. The process adds to the aesthetic quality of the image as well with scratches and fades that creates an ephemeral quality and ghost-like images. These marks, or as Mann puts it, “perfect flaws” put the process in the forefront (Longmire). Daguerreotype seems to be as important to the final piece as the subject itself.

However, in another series of Flesh and Spirit, Body Farm, in which Mann photographed at the grounds at the University of Tennesee’s Forensic Anthropology Center, the use of daguerreotypes furthers the narrative and adds another dimension to it without eclipsing the subject. The Center, also known as The Body Farm, is an open, rural area in which unidentified bodies naturally decompose so forensic tests can be practiced and developed. In taking these images with daguerreotypes, Mann is recording the passage of time and the decomposition the bodies are experiencing. The process itself adds a quality to the produced image of decay, further reinforcing the subject. In this series, the process perfectly aligns with the subject without creating a separate narrative based on daguerreotype. Mann has been a reputable photographer for decades, however, by returning to an abandoned process, she is able to create new levels within the stories she tells.

Modern artists are using the daguerreotype process, along with other out-dated processes to move the hands-on aspect of photography back from the cliff of its disappearance, towards to a personalized experience. Each flaw that is visible in the final print helps to tell the story of the image capturing process. Humidity, altitude and temperature all affect a daguerreotype in different ways as well (Mallin, 68-73). The image, which is a record of a period of time, not just an instant, tells the story of the artists as much as the subject in that time period. It allows intimacy with the medium that’s unavailable with digital photography (Harris, 64-68). As Irving Pobboravsky states, “unpredictability provides the gift of chance” (Rexer, 72-85). For those that embrace this unpredictability, the opportunities for meaning are endlessly supportive of the narratives the images themselves create.

The process of creating is undoubtedly important to the meaning of the final product. With daguerreotypes, the process is visible in the final product but with in other mediums, the process is sometimes taken for granted. In January of 2011, The Process Museum opened in a rural area outside of Tucson Arizona. This 70,000 square foot facility’s aim is to show the physical and mental process of the artist in creating. And they appear to do so to an almost ridiculous degree: there are sixteen rooms devoted to one artist, and 712 by another. To even visit the museum seems like a labor-intensive process: one has to make an appointment ahead of time for a specific two hour tour that is held Tuesdays and Thursdays at 10 am only (The Process Museum).

The Process Museum illustrates the idea that the final piece is not more important than the process by which it was created. However, is there a point when the process eclipses the creative integrity of a piece of artwork?

Sources:

Alternative photography: Unfrozen in time. The Economist v. 378 (February4 2006) p. 75-6

Fleischmann, J. The daguerreotype revival. Discover v. 23 no. 2 (February2002) p. 52-4.

Harris, J. Aura fixation: old technology for new photography. Art On Paper v. 5 no. 3 (January/February 2001) p. 64-8.

Longmire, Stephen. “LEAVES OF GLASS” Sally Mann: Proud Flesh. Afterimage. New York: Aperture/Gagosian, 2009. 64 pp. Web. 28 Feb 2011. http://www.faqs.org/periodicals/201001/1951137931.html.

Mallin, J. Photography the Hard Way [Work of C. Schreiner, J. Quinnell and R. Kendrick]. Popular Photography & Imaging. v. 70 no. 4 (April 2006) p. 68-73.

Osterman, M. How to See a Daguerreotype. Image (Rochester, N.Y.) v. 43 no. 2 (Autumn 2005) p. 12-15.

Pictorialism. Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1911 Edition . Web. 28 Feb 2011. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/752375/Pictorialism.

Poyner, Rick. The Floral Dutchman. I.D. Magazine. June 2003. pp58-63.

Rexer, L. Chuck Close: daguerreotypes. Aperture no. 160 (Summer 2000) p. 40-9.

Rexer, L. Photography’s antiquarian avant-garde: reviving long-obsolete

processes. Graphis. v. 55 no. 320 (March/April 1999) p. 72-85.

Rexer, L. Photographers move forward into the past. New York Times (Late New York Edition). (September 27 1998) p. 39 (Sec 2).

Robert, Molly. Modern Family. Smithsonian Magazine. May 2005. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/Model_Family.html.

Sally Mann. The Gagosian Gallery. Web. 28 Feb 2011. http://www.gagosian.com/exhibitions/980-madison-2006-03-sally-mann/.

The Process Museum. Web. 2 May 2011. http://www.processmuseum.org/.

Leave a comment